Quarter Moon - Sample

THE BATTLE OF NEWLANDS

Chapter 1 – The Battle

A heated conversation filled the horse drawn carriage throughout the final mile to the battle ground. A journey that was a battle in itself along a cart-rutted track traversing the steep hillsides into Newlands Valley. Edward Creasey was not an optimist. He wasn’t a pessimist either. He insisted his approach to life was one of calculated risk, of planning, contingencies. “Arming oneself with the best available facts and making a considered judgement thereon,” he said.

“Thereon. Archaic language. Proof, Mr Creasey, that you live in the past.” Reverend Charles Barrington was not interested in Creasey’s proposed investment and neither were Patrick Sommerby, a chemist from Lancaster, and Mr T.P. Williams, a gentleman from the Midlands.

Creasey continued. “Steam locomotives, gentlemen, would have delivered us to this spot several hours earlier than our present condition. Look at the place. Several drops of rain turn the roads into quagmires. How they fight in these conditions is beyond me.”

“Several drops of rain and hundreds of coaches that have been coming along here all day.” Sommerby had a copy of the event programme: The Battle of Newlands – a Grand Spectacle Pitching the Pagan Army of the Danes Against the Christian Saxons of Leofric of Cumberland. “Three shillings for a front row position. Fourpence to sit further up the hillside. All views guaranteed.”

“Please, Mr Creasey,” said Reverend Barrington, “I hardly think Mr Trevithick’s invention would fare any better along these wretched upland routes. And what of the pagans? How would they use the transportation? They can barely utilise a metal field plough.”

“Respect, gentlemen, respect.” Creasey ignored the rusting skeletons of farm machinery abandoned across the flooded fields. “I doubt the Saxons or the Danes will have time to utilise the opportunities of steam locomotion. Indeed, they may have struggled with horse-drawn ploughs as soon as they were left alone with them, but we are not as hamstrung as they are. We have a great opportunity here to invest in the future and reap great rewards. Trevithick is months away from perfecting the steam engine and combined with the new lines opening everywhere, and my God I wish we were on one now-“

“Manners, Mr Creasey.”

“Sorry, Reverend. How I wish we were on a plateway now instead of heaving through this wretched mud.”

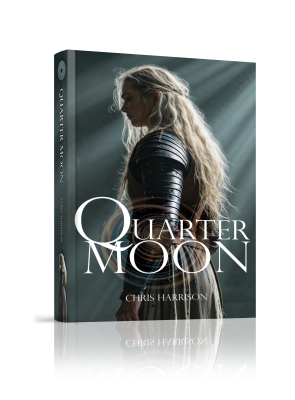

“Enjoy the firebreathers,” announced Sommerby’s programme. “Marvel at the Saxon Warrior Queen Beatrische.”

“No place for a woman,” said Reverend Barrington. “Proof, gentlemen, of the savagery of these people.”

The back of the programme had an unrecognisable map of the area. “There won’t be much of a view with all this forest.”

“Won’t they be occupying the fell side, Mr Sommerby?” Williams leaned across to inspect the map.

“It’s quite steep. No terrain for a lady, I would have thought. Oh, hang on.” There was a footnote. “Assistance offered to ladies requiring access to the upper viewing areas. Well there you are.”

“Still doesn’t look right to me,” said Reverend Barrington. He sat on the valley side of the coach looking across fields that plunged towards a wooded stream. “I suppose it is a rather extensive area.”

“It will have to be, if the amount of transportation is anything to go by,” said Sommerby.

Outside, in the drizzle, the coachmen struggled to help the horses pull their grumpy cargo and the weight of unnecessary baggage through the rutted slime. The narrow track wasn’t designed for two coaches side by side and the obstacle of oncoming travellers added to the misery. Both sets of passengers were forced to wait whilst the coachmen agreed on how they might pass each other. One of the opposing coachmen approached the carriage, dodging the mud that threatened to suck the boots off his feet.

“Good morning, gentlemen.” He tapped the peak of his hat. “I don’t wish to be impertinent, but if I were you I’d turn back.”

“Turn back,” said Creasey. “We’ve only just arrived.”

“Is there space to turn around?” said Sommerby.

“There’s an area a few yards ahead where you can turn around, yes, sir. I wouldn’t advise such a thing, gentlemen, but the crowds up ahead are quite big. Some organisers are concerned about the battle getting too close to the crowds. My clients have decided the risk is too great and are heading back to Keswick.”

“Perhaps we’ll make a decision when we are a little closer,” said Creasey, “but thank you for the advice, sir.”

“Very good, sir.” The coachman cocked his head a little and raised his eyebrows. “Bare it in mind.” He muttered to the coachmen struggling with Creasey’s carriage and shared a concerned look up the valley towards the growing sound of clashing metal and shrieking warriors.

The tenacity of the mud could have been a warning to stay back and keep a safe distance. The cries and screams of conflict had been audible for several minutes and every violent expression of anguish was met with exuberant gasps of onlookers. If the mud allowed, the crowd would soon be joined by four more eager voyeurs.

Mr Williams leaned out of the coach window. “Do we continue on foot?”

“No, you’re all right, sir. We’ll have the horses out in a moment. A touch slippery underfoot here.”

“A touch slippery, sir? Resembles a swamp. Where are we?”

“Less than five minutes from the show ground, sir.” The horses huffed and honked and heaved the coach forward, tugging Mr Williams’ head back into the frame of the window.

“Imagine if that were an axe, Mr Williams?” said Sommerby.

“What should we do? Heed the advice and turn back?” said Reverend Barrington.

“Let us see for ourselves,” said Sommerby. He read from the pamphlet again. “The greatest battle yet seen in the North of England.”

The carriage lurched forward. Reverend Barrington sighed. “Perhaps you have a point, Mr Creasey. About this steam locomotive.”

“I do have a point, gentlemen. I’ve been telling you since York, Trevithick’s steam locomotive is the future. There is good, honest money to be made in supporting his endeavours.”

“Edward,” Sommerby put on his gloves and brushed his hat, “Trevithick’s steam engine broke down. That thing rattling down the streets was as dangerous as any mob of marauding Danes and Saxons. Now consider today. I have placed a wager on a Saxon victory which will,” Reverend Barrington closed his eyes, “I’m sorry to be discussing wagers before a man of God, Reverend, but at least I’m being honest. My wager will produce an immediate reward.”

“If the Saxons win,” said Creasey.

“Yes, if the Saxons win, granted, but if I were so inclined I could lay a wager every day. Several. The odds are greatly in my favour.”

“There are no favours for adventurers, Mr Sommerby.”

“Please, sir, I have never indulged in lotteries. The race track and the card table is where I take my calculated risks. And the certainties are far more favourable than Trevithick’s clanking monsters.”

“And when the day of judgement comes, Mr Sommerby?” Mr Williams knew Reverend Barrington would know the answer.

“Indeed. You will repay your winnings sevenfold, Mr Sommerby. At least Mr Creasey’s investment is an honest endeavour.”

“It is a foolish endeavour.”

The coach stopped again when the opposing travellers came alongside. “You’re going on to the show ground, gentlemen?” said a man through the window of the coach.

“Yes. We’ll decide when we get there if it’s safe to remain.”

“Take our advice. Get out now. There’s no organisation to be spoken of. Disaster waiting to happen. Drive on, coachman.” They bumped and trundled away leaving the track ahead clear of traffic, but no less accessible.

When the coach finally arrived at its destination there was uncertainty where it should stop. Space was exhausted. Hundreds of horses and carriages, carts and luggage crammed the fell side, and where space remained it was filled with waiting coachmen sat on trunks and the rooves of the carriages to obtain a higher view of the battle in the valley below. Beyond the carriages above the track was the crowd, a vast meadow of heads, hats, bonnets and parasols, and below the track more people forced to sit less than a hundred yards from the battle’s ragged edge.

Sommerby stepped out of the carriage into a din of such ferocity he climbed back into his seat. “Heavens the place is Bedlam.”

The conclusion to the wretched journey was a windy outlook half way up a hill. On a plan the layout would have been sufficient. The sideshows beyond the carriages, the crowd beyond that. Newlands Valley had the length to accommodate thousands and the fell side above the track stretched towards the miserable underside of cloud from which the drizzle drifted and soaked into overcoats and blankets.

Down in the valley bottom, where a stream twisted through dense woodland, the battle was contained within several fields. The crowds wanting their money’s worth had condensed into a fattening mass of bodies creeping closer and closer to the trees and the carnage.

“For the love of God the organisers have no control,” said Creasey. “They need to spread people out down the valley.”

“Judging by the bodies down there the battle is coming up the valley.” Sommerby assessed the tactics. “The crowd is moving with the conflict, but there isn’t space.”

“Do we stay or go, gentlemen?” said Creasey. The decision was made for them. Several new carriages arrived blocking them in.

Stewards working for the organisers wandered through the crowd. Harassed and bothered by the disorder, they tried to move the crowd farther up the hill, but it was slow progress and those already in position above the track had no desire to move. Under a threatening sky, as colourless and chaotic as the battle in the valley below, the gathered masses shifted with great reluctance, picked up their bags and baskets and called for absent children recreating the battle. Groups of boys and girls fought with wooden swords and flung branches at each other.

“I don’t like any of this, gentlemen,” said Mr Williams. “Looks to me like the battle may spread beyond the valley floor.”

“I’m inclined to agree with you,” said Creasey. “We can’t move the carriage, but we can walk to a safer position.”

They found the track, stumbled along the slope and ignored the beggars. Reverend Barrington searched his pockets and found his purse and a handkerchief, blew his nose and walked on.

To the right, the hill dropped away to the battle, the slope filled with the growing audience as large and eager as any seen at the circuses in London. To the left, jugglers and acrobats relocated to the safety of the open space. Men balanced on large balls. Women assisting third-rate magicians distracted those that needed a break from the gory display in the valley. Roasted food warmed the insides, ale dulled the senses and those with any faculties still in place gathered around the bookmakers.

Creasey sighed. “We’ll leave Mr Sommerby to assess his investment in today’s proceedings.” He recognised a small group of men and called out. “Not the best day to be out on the hills, gentlemen.” The men took great care to avoid the deeper puddles of mud and stepped over to say hello.

“Mr Creasey, I thought you’d be holed up in York rather than out here watching the pagans slaughter each other again.”

“Today is a little different, Mr Barrowclough. My friends, Mr Williams and Reverend Barrington. Mr Earnest Barrowclough. A delegate for the Anglo-French Cultural Service.”

“An impressive title,” said Reverend Barrington.

They all shook hands. “A mere trifle. We travel abroad and report on events, advise businesses wishing to trade with a country increasingly in turmoil.”

“You’ll feel quite at home here then.” Mr Williams chuckled.

Barrowclough glanced down at the battle. “Yes, quite so. I don’t know about you, gentlemen, but the organisers seem to have made a pig’s ear with all this. See there, those people are an arrow shot away from injury. One year after the Act of the Union and they’re still hacking each others heads off. It says a lot about the new Protocols.”

“Indeed it does,” said Creasey. A distant Saxon lined up his target and hurled a spear at a Dane. The spear entered his back, emerged from his chest and the Dane fell without a sound.

Barrowclough saw it too. “Come, Mr Creasey, I know you share the ideals of the French, but the advancement of technology isn’t everything. Look at them down there. If we were still interacting with them our own soldiers would be fighting the Saxons or fighting the Danes. The pagans holding their rifles the wrong way round.”

“That is a myth, Mr Barrowclough.”

“It may well be, but let’s not be distracted by our differences or the growing racket.” Barrowclough raised his voice. “Our group has just returned from a trip to Paris. The talk there is that the dreadful lunatic Napoleon wants to crown himself emperor. Now as a military development that is extraneous to our considerations, but as a historical development it begs the question where did he get such an idea?”

The answer was slow to arrive. “I don’t know. Perhaps you can enlighten us.”

Barrowclough pointed at the clouds.

The dense blanket of rain cloud rolled over, flattened the light and pitched the elevated countryside into depression. Greens turned to grey and the only colours strong enough to hold up were the bright primaries of the side shows and the clowns entertaining the children. But now and then, when the cloud formation broke, the level underside of a giant disc would peek through the misery. Its dull white surface reminded everybody on the ground they were being observed.

“Why would they want Napoleon to become an emperor?” said Creasey. A tiny raindrop hit him in the eye.

“Meddling, Mr Creasey. Meddling. During the last Quarter Moon event they spent years interfering in our affairs, the affairs of the Saxons and Danes, anything to keep us apart and look at the consequences. When it suited them they forced great political change. How else did Catherine the Great become Empress of Russia?”

“I still don’t believe that’s true,” said Creasey.

“It is documented, Mr Creasey. In the discussions about the Protocols during the second event, Catherine objected. She was a beneficiary of such collusion, but those from the future told her straight. We put you where you are, we can take it away again. Meddling, Mr Creasey. They have no problems of their own, so entertain themselves by meddling in our affairs. And we find ourselves in this situation a third time and their actions are becoming an influence on those with ill intentions. Learned men are debating peace and liberty and at the same time Saxons and Danes are slaughtering each other.”

“I’m sorry, Mr Barrowclough, are you and your service for or against the Protocols? I’m not quite sure.”

“Neither, Mr Creasey. It is all relative. Consider this. If Leofric, Ealdorman of Cumberland perishes today his wife has no future of any worth. How can we debate humanity when we overlook such personal disasters and, and, pay good money to see it.” His indignation brought on a coughing fit.

“Well perhaps my good friend here can tell us if the good lady has a future or not.”

Sommerby moved away from the bookmakers, placed a betting slip in his satchel and joined Creasey. “Something the matter?”

“The Ealdorman’s wife, Patrick. Will she survive today’s battle?”

“Judging by the odds on a Saxon victory I would say a rather easy win and a healthy future.” He retrieved the betting slip.

“And how much will that cost you?”

“Ten shillings.”

“Ten shillings?” Creasey gasped.

“Your investment in Trevithick will be far more than that. And with a less predictable return.”

On the other side of the valley a fresh group of Saxons pushed down the slope and crossed the stream. The Danes weren’t expecting the move and looked for space to retreat and regroup, but the space was occupied by the crowd.

Creasey shook his head. “Perhaps you should place a wager on Napoleon becoming Emperor of France.” Sommerby laughed. “We have inside information, do we not, Mr Barrowclough?”

Distracted, Barrowclough’s voice quivered with nervous concern. “I am not telling you all this just so your friends can make an agreeable return, Mr Creasey. I really do think we should move on, gentlemen. I fear the battle is heading straight towards us.”

The growing noise overtook them. Warriors surged along the edge of the fields where they met the trees. Faced with increasing Saxon numbers, Danes thrashed their opponents, but axes were useless against spears and arrows. Unable to move north or east their only hope was south and west. But the south was blocked by the incoming crowd, herded into position by stewards with no clue where they should go. And the east was even more inaccessible. The slope, the people, the carriages and horses, the tumblers and strongmen. All of them a wall.

But not an impenetrable wall.

A volley of arrows came over the tree tops. A deadly rain of death that struck Dane and 19th century onlooker without discretion. Danes fell in agony, men and women panicked, struggled to heave themselves off the ground and back up the slope, their progress blocked, the organisation useless.

Women screamed. Their husbands dragged them inches from where more arrows rained down on them. Children disappeared beneath bodies pushing and heaving to move up the slope. The stewards vanished in the melee, some tripping, others pushed over, one hit by an arrow that passed through his head.

“Get to the track, gentlemen.” Creasey pulled Sommerby along. Reverend Barrington ducked, stray arrows slicing through the air inches above his head. Barrowclough stumbled, slid around in the mud, stayed on his feet and achieved a few more yards towards safety.

Behind them the chaos continued. A grotesque mixture of battle cry, agony, the deranged cacophony of women, the thud of thousands of bodies surging across the ground. The panic expanded exponentially. The battle moved into the crowd. Stewards lost control. Every man had to look out for himself, every father lost sight of his children, every husband struggled to find his wife. The arrows were joined by spears. The Danes fought through the crowd, parried Saxon swords, fell at the feet of men and women trying to evacuate the carnage that had once been a distant spectacle. Now it was all around them.

“There’s no way out.” Sommerby, his voice lost in the noise of battle, was stuck in mud that covered his shins. Creasey tried to help, but the velocity of warfare consumed them. The crowd were engulfed by the fury, disappeared behind men and women killing each other. Up close, hand to hand, screaming and howling, Saxon stabbed Dane, Dane axed Saxon. Two against one. Heads smashed. Eyes gouged. A sword slashed a Dane’s face until his jaw hung loose. Creasey was crushed between two grappling men. An injured arm came away and the bleeding stump pushed into Creasey’s cheek.

Reverend Barrington called out when he fell, trampled by the stampede. A fallen Dane was set upon by two Saxons with swords and daggers, slashing and stabbing until Reverend Barrington was soaked with the blood and intestines of the body.

“Patrick, for God’s sake forget your bag, protect your head.” Creasey took a punch to the jaw.

The Dane with the fist blinked, pulled his second punch when he saw Creasey’s shock. A sword burst through his throat. The Saxon behind him struggled to remove the sword and he fell to an axe blow that split his head in two.

Creasey vomited. Arms grabbed his waist, gripped his overcoat and hauled him through the overwhelming mass of arms and shields. Battered and shoved, they had no choice but to go where the battle moved. Swirling and pitching, blades within inches of their ears, coat sleeves ripped apart, another spray of deep red blood across their faces. An ear bitten off. A broken axe head left in a metal helmet, the head detached from the body. The stench of sweat, urine, all manner of bodily waste replaced the deafening roar of hatred.

Unable to breathe, Creasey hung on to the figure he hoped was Sommerby. They curled up on the ground, covered their heads. Waited for the fighting to move on. And then the heat of fire joined them.

Danes regrouped. Pulled themselves back from the Saxon front line. A merciful opportunity appeared and Creasey rushed after Sommerby when he sprinted for the track. They pushed through the oblivious Danes who pulled together, formed a shield wall and stepped forward.

“There are more Saxons than the organisers expected.” Sommerby gasped for breath. “They predicted an army of six hundred versus four hundred Danes, but there are clearly more than that on both sides.”

The relief lasted a moment. Another surge pushed the shield wall backwards. Creasey and Sommerby dashed up the slope, but the gap remained constant. The arrows flew again, but this time they burned. Small missiles of fire dropped into the gathered mass of Danes and the grass behind them. Clothing ignited. Warriors squealed like pigs, squirmed out of the lines, flailing and writhing. More arrows, more fire. The shield wall disintegrated. The Saxons charged again.

They split the crowd still stuck on the slopes. Ran over bodies of 19th century men, women and children. Those still able to move dashed towards the stream like terrified sheep.

The front rows of the crowd had paid three shillings to be swallowed up in the warfare. A Saxon rode into the battle. The Ealdorman, Leofric, ahead of a small cavalry of horseback warriors. The velocity of battle increased. The violence worsened. Desperate to avoid certain death Danes sprinted in every direction. The Saxon bloodlust sensed victory, became blind to the clothing and the accents, the top hats and bonnets. Gentlemen and ladies scurried for sanctuary, children were swallowed by the mud.

Now the noise was too much, the grunting and screaming. Creasey and his investor friends raced along the track, but were still overtaken by men in leather armour and chain mail, swinging and thrusting their hideous weapons. The scattered crowd followed gravity into the swamp of the valley bottom and in the enveloping mud became indistinguishable from the soil-soaked warriors around them. Unprotected by modern clothing, they were slashed and stabbed, beaten and clubbed. The view came and went between rushing Saxons, fleeing Danes, huge warhorses that spread thunder across the ground. The haze of fire and the stench of dead flesh made Creasey’s eyes water.

A man begged to be spared. He was killed by a single axe blow. Two men held a woman, protecting her, but they were three more victims for Saxon spears. To the left another man crawled towards the stream and was hacked to death by four Danes. Beyond him, amongst the burning tree trunks a pleading woman was dragged by the hair against rocks and run through by Saxon swords. All the victims fee-paying visitors.

Sommerby wept. Kneeling now, he cried out for the carnage to stop, but his cries were ignored. There was no end to the slaughter until a lone Saxon displayed a decapitated head. He picked up the bonnet it had once worn and glanced across the battlefield.

A horn blew, the intensity of the fighting diminished. Fighters stopped, looked around them, examined the appalling scene at the foot of the hill. A small lake of blood expanded around the submerged corpses of unarmed men and women. The pile of bodies lay shoulder high.

A huge Dane stood alongside Creasey. “What is this?” Two Saxons waited for Creasey’s clarification.

“Should we go on?” said another warrior, “should we fight?”

Years had passed since Creasey last stood so close to Saxons and Danes. They were bigger than he remembered, incomprehensible, no less filthy, covered in blood, their clothes torn, shields shattered to matchwood. He stuttered. “This is a tragedy, gentlemen. We should help if we can.”

“We should not.” Sommerby gasped. “It is the stewards’ responsibility.”

“I don’t think there are any stewards left standing, Patrick.”

“Shouldn’t you take their confessions, Reverend?”

“Pagans? Certainly not.”

“They’re not pagans, Reverend, they’re Christians.”

With dread and a great deal of reluctance, Reverend Barrington made his way down the hill followed by Creasey and Sommerby. They stepped over dismembered Saxon corpses, headless Danes; accidentally kicked a stray hand or a leg concealed by the long, untrampled grass. The farther down the slope they trudged the more modern the bodies became until they were on the edge of a field of dead and dying men and women. The burgundy blood ankle deep. The lifeless bodies piled like unwanted rubbish.

“I see no one still alive,” said Reverend Barrington.

“This was long toweard.” A Saxon dragged his colleague from under the modern bodies. His heavy accent barely understandable, but his anger clear. The crowd, the voyeurs, the ghouls, paid money to watch the Anglo-Saxons confront the Danes in battles to the death and until now had done so from a safe distance.

Another cry went up and Creasey’s stomach fluttered fearing a resumption in the fighting, but the cry was the appearance of the Ealdorman’s horse, its rider gone. Back up the hill a group of Danes wrestled with their enemy until the body of Leofric was pulled from the long grass and carried down to the Saxon group.

Creasey saw her first. Dressed for war, a woman, blood-smeared and filthy, a deep wound splitting the seam of her shoulder armour. She stumbled through the mud and grabbed at the body. Her husbands body.

“Is that her?” said Creasey.

“Beatrische. I believe it must be,” said Sommerby.

There were no tears, no hysterics, just a fevered attempt to revive what couldn’t be revived. The limp body was just a vessel for the organs and muscle, tissue and bone. The man gone, the husband killed. His wife, Beatrische, shook him, punched him and then buried her head in his chest and sobbed.

If Creasey’s plans had been fomented one year earlier, they would have arrived several hours sooner and sat in the front row waiting for certain death, brought down by an axe or a sword, pierced by a stray arrow. They would have been drowned in their own blood or watched their limbs roll down the hill. In that moment, when Beatrische lifted her blood soaked head, she caught Creasey’s attention and stared at him, blinked, her features consumed by soil and dread. Not the dread of bereavement, but the dread of a dangerous future. Her husband dead she was now the target, the focus. Who would help her now? Who would invest in her future?

Overcome by the event, Beatrische dropped to the ground. Creasey and Sommerby pushed forward to help. “Remember the Protocols, gentlemen,” called Reverend Barrington.

“To the devil with your Protocols. She needs help.” Creasey found a small huddle around Beatrische. Filthy water was thrown on her face, but she remained cold and semi-conscious, muttering and mumbling, eyelids flickering.

“Here,” Sommerby pulled his satchel off his shoulder and rummaged for a bottle. “We must treat this dreadful wound. Water, man. Water.” More filthy water was poured over the gaping slash across Beatrische’s shoulder. Sommerby tugged the leather and linen apart and soaked as much of the blood as his handkerchief could hold. Creasey offered his own handkerchief, Sommerby soaked it in disinfectant and held it firm against the wound.

“You should not do that, Mr Sommerby.” Reverend Barrington was the only objecting voice. “The Protocols exist for a reason. Unintended consequences-“

“Your Protocols. It’s a small amount of disinfectant. What can possibly go wrong? Be away with you if you’re not willing to help.”

Another downpour revived Beatrische enough for her to make sense. Her words were soft, her accent heavy, dialect peculiar. She asked about a daughter, she asked about her husband. No one answered. Aware of Reverend Barrington watching the group, Creasey suggested Beatrische be taken back to her castle and cared for.

“Take this with you.” Sommerby poured some of the disinfectant into a small empty bottle.

“That is against the Protocols, Mr. Sommerby.” Reverend Barrington tried to speak again.

“You didn’t see me do this, did you?” said Sommerby. “Put it on the wound. It will stop infection. It needs to be stitched, Edward.”

“We can’t do that here. Unless you have a needle and thread. Do you have a needle and thread, Reverend?” Reverend Barrington plodded back up the hill (and tripped over a corpse hidden in the long grass).

Beatrische mumbled again. Creasey bent closer to hear. “What shall I do?” she said.

“I don’t know what you mean. I’m sorry. I’m sorry, we can’t do more to help.”

“His title . . . now mine.”

“Title?”

“His title. . . . “

She was delirious and rambling, muttering words of title, leading, her husband’s work, her people, her daughter. But none of it made sense to Creasey.

There was some relief to see Beatrische back on her feet. She needed support and walked with the effort of a drinker on the verge of collapse. She was carried away on a cart down the track, through the quagmire and off into the trees and darkness as dense as her future.

“I presume you’ll be recording this dreadful spectacle in your diary, Edward?” Sommerby held a glove across his nose and mouth.

“Yes. Yes, I will. People must know what happened today, Patrick. People will pay good money to read about what happened today.“